Once upon a time, when computers were just starting to become part of everyday work, people were trying to figure out how to use them to help managers make better decisions. At a university called the University of Minnesota, some really smart researchers decided to test this idea in a series of experiments. These experiments became known as the “Minnesota Experiments,” and they were a big deal in the world of Information Systems.

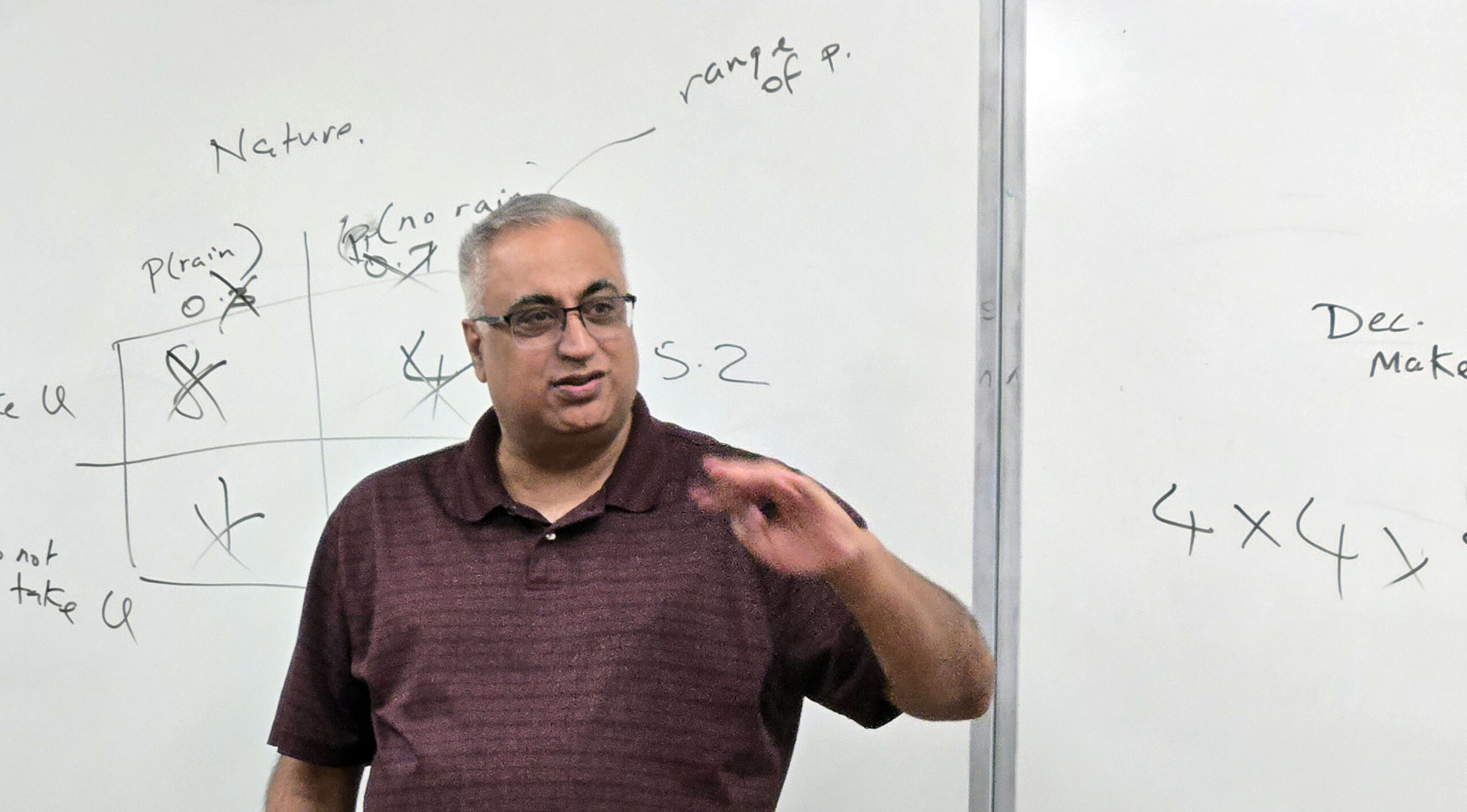

So, what did they do in these experiments? Imagine you’re in a classroom, and the teacher gives you a decision-making task. Maybe you have to decide the best way to run a company or solve a problem. To help you, the teacher gives you different types of information. Some students get tables full of numbers, graphs, and charts that break everything down logically. Others get stories or pictures that give them a sense of the whole situation without diving into too much detail.

Now, each student in the experiment has a different way of thinking, or what we call a “cognitive style.” Some students are “systematic” thinkers—they like the charts and numbers because they can go through the information step by step. Others are “intuitive” thinkers—they prefer the stories because it helps them see the big picture all at once.

The researchers wanted to see how well people made decisions based on the kind of information they were given. They thought that if the way information was presented matched a person’s thinking style, they’d make better decisions.

So, they ran a bunch of these experiments with students and sometimes employees, giving them different kinds of information and measuring how good their decisions were. Their goal was to figure out how to design computer systems that could present information in a way that fit people’s thinking styles. If they could do this, they believed it would help people make better decisions.

This was a big idea at the time, and the University of Minnesota became famous for these experiments. Many researchers who worked on these studies went on to become leaders in the field of Information Systems.

But then came George Huber, a well-respected expert. Huber looked at all this research and said, “Wait a minute, is this really working?” He pointed out some big problems. First, the results from these experiments were all over the place—some showed that cognitive style mattered, and some didn’t. Second, the way they were measuring people’s thinking styles wasn’t always accurate. Third, there were way too many personal traits to consider, not just cognitive style. He said, “How are you going to design systems for every single type of person?”

Huber’s arguments were so strong that after his paper came out, the Minnesota experiments mostly stopped. Instead of trying to design systems that fit different thinking styles, people started focusing on making systems flexible—so anyone could use them, no matter how they thought.

And that’s the story of the Minnesota experiments. They were an important step in trying to figure out how to help people make better decisions using computers, but in the end, researchers realized that creating systems flexible enough for everyone was the better way to go

Leave a Reply