Anthony Giddens’ structuration theory has become a fundamental framework in organizational studies for understanding the reciprocal relationship between human actions and institutional structures. While structuration theory was originally not about technology, Wanda Orlikowski and Daniel Robey extended it to the realm of Information Systems (IS) to explore how information technology (IT) and organizational structures interact. They demonstrated that IT is not merely a passive tool but actively shapes—and is shaped by—organizational actions and structures.

This comprehensive article will delve deeply into Giddens’ original structuration theory, examine how Orlikowski and Robey expanded it to include IT, and explain the two diagrams in their paper. The article will emphasize how these concepts form a “meta-theory”—a broad framework from which many specific theories can be derived, offering lasting value for studying dynamic organizational processes.

Structuration Theory: The Foundation by Anthony Giddens

At the heart of structuration theory is the duality of structure—the idea that structures (such as rules, norms, and resources) shape human actions, but they are also produced and modified by those actions. Structuration theory challenges static views of organizational structures, asserting instead that they are dynamic, evolving through the actions of individuals who work within them.

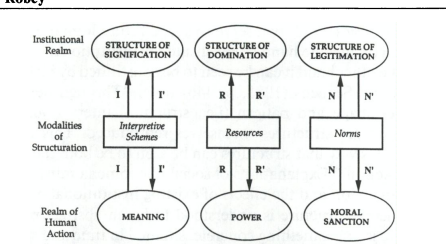

Giddens’ theory comprises three main levels:

- Institutional Realm:

- The institutional realm represents the broad, overarching social structures that guide and constrain individual behavior. In organizations, these structures include:

- Structure of Signification: This structure represents shared meanings and interpretations that guide behavior. It defines what is important and provides a shared language or set of symbols through which individuals make sense of their world.

- Structure of Domination: This structure pertains to power and control, often tied to resource distribution. It explains who has authority, who can command resources, and how power is exercised within the organization.

- Structure of Legitimation: This structure includes norms and values that define what behaviors are acceptable within the organization. It establishes a moral code, setting the rules for what is seen as right or wrong.

- The institutional realm represents the broad, overarching social structures that guide and constrain individual behavior. In organizations, these structures include:

- Modalities of Structuration:

- Modalities are the “linking mechanisms” that connect the institutional realm with individual actions, making it possible for structures to influence actions while being influenced by them. The modalities include:

- Interpretive Schemes: These are frameworks that help people interpret and make sense of their environment, linking to the structure of signification. For instance, an employee may interpret feedback from their manager as either constructive or punitive, depending on their interpretive scheme.

- Resources: Tied to the structure of domination, resources represent tools, knowledge, and assets that people use to exert influence or accomplish goals. Resources can be economic (like funding) or symbolic (like expertise).

- Norms: Linked to the structure of legitimation, norms are informal or formal guidelines that dictate acceptable behavior. They influence how individuals perceive what actions are appropriate within the organization.

- Modalities are the “linking mechanisms” that connect the institutional realm with individual actions, making it possible for structures to influence actions while being influenced by them. The modalities include:

- Realm of Human Action:

- This is the level at which individuals act within the constraints and possibilities offered by the institutional realm. Here, individual actions reflect:

- Meaning: Influenced by the structure of signification through interpretive schemes, meaning represents what individuals see as significant. For example, a PhD student may view attending academic conferences as highly meaningful if the academic institution places value on such events.

- Power: Shaped by the structure of domination through resources, power reflects the ability of individuals to affect others within the organization.

- Moral Sanction: Guided by the structure of legitimation through norms, moral sanction refers to the approval or disapproval of actions based on the organization’s values.

- This is the level at which individuals act within the constraints and possibilities offered by the institutional realm. Here, individual actions reflect:

In this model, individual actions both reflect and reshape the institutional realm. For instance, if employees repeatedly challenge an outdated norm, they may succeed in changing it, thus altering the structure of legitimation itself. Structuration theory therefore suggests that structures are both constraining and enabling—they limit actions but also provide a framework within which actions are possible.

Diagram 1: The Core Framework of Structuration Theory

The first diagram in Orlikowski and Robey’s paper represents the core of Giddens’ structuration framework, illustrating the interplay between the Institutional Realm, Modalities of Structuration, and the Realm of Human Action.

- Institutional Realm (Top Level): This layer contains the structures of signification, domination, and legitimation. Each of these structures provides a context or framework within which individual actions are performed.

- Modalities of Structuration (Middle Level): These modalities serve as the mechanisms through which institutional structures influence individual actions and, in turn, are modified by those actions. Interpretive schemes mediate the structure of signification, resources connect to domination, and norms are linked to legitimation.

- Realm of Human Action (Bottom Level): This is the level where individual actions take place within the context of meaning, power, and moral sanction. People act based on their interpretations of significance, their power dynamics, and the norms they recognize.

The diagram’s arrows illustrate the dynamic feedback loop between the levels: individual actions are shaped by institutional structures at the top, but those actions can also feedback to alter these structures over time. For example, individual reinterpretations (mediated by interpretive schemes) can shift what is considered significant within the structure of signification, affecting the shared meanings in the organization.

Extending Structuration Theory to Information Technology: Orlikowski and Robey’s Contribution

While Giddens originally conceived structuration theory without specific reference to technology, Orlikowski and Robey recognized that in modern organizations, information technology (IT) plays a fundamental role in shaping and being shaped by organizational actions and structures. They incorporated IT into the structuration framework, creating a model that demonstrates how technology both influences and is influenced by organizational behavior.

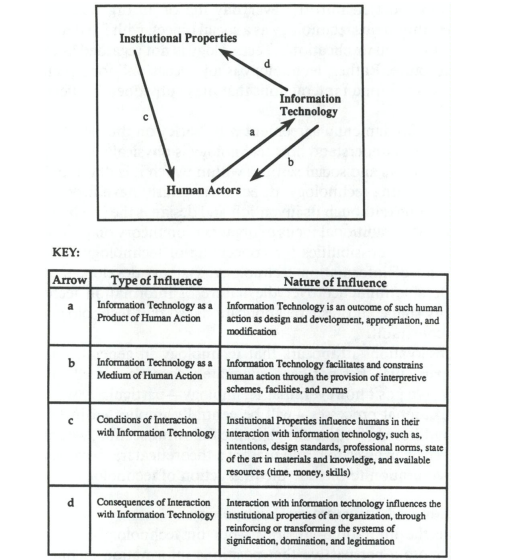

Orlikowski and Robey’s model introduces four types of interactions between Institutional Properties, Information Technology, and Human Actors:

- IT as a Product of Human Action (Arrow A):

- This arrow illustrates that IT is created by humans. IT systems reflect the intentions, goals, and constraints of the people who design, develop, and implement them. For instance, a knowledge management system may be built to capture best practices within a consulting firm, embodying the values and objectives of the organization. IT, in this sense, is a “product” of the institution’s existing structures of signification, domination, and legitimation.

- IT as a Medium of Human Action (Arrow B):

- Once created, IT becomes a medium through which human actions are facilitated and constrained. IT systems shape how people interact, work, and communicate, but they also impose certain limitations. For example, a project management tool may structure the way tasks are assigned and tracked, requiring employees to follow specific steps. Thus, while IT enables certain behaviors, it restricts others, reflecting both the enabling and constraining nature of technology.

- Conditions of Interaction with IT (Arrow C):

- Organizational context influences how people interact with IT. Institutional properties like resource availability, policies, and cultural norms shape how individuals use IT systems. For example, an organization might limit access to certain features in a software system to comply with data privacy regulations. This arrow highlights that organizational structures affect the conditions under which IT is used.

- Consequences of Interaction with IT (Arrow D):

- The interaction between human actors and IT has a feedback effect on organizational structures. Over time, how IT is used can reinforce or reshape institutional properties. For instance, if employees begin using a communication tool to bypass traditional reporting lines, this may alter power structures and change what is seen as acceptable communication practices. IT thus contributes to the evolution of organizational norms, values, and power dynamics.

Diagram 2: Structurational Model of Information Technology

The second diagram in Orlikowski and Robey’s paper visually integrates IT into the structuration framework, illustrating the interactions between Institutional Properties, Information Technology, and Human Actors. This diagram builds on the first by adding IT as a dynamic player, reflecting how technology operates within the structuration framework.

Here’s a detailed look at each arrow in the diagram:

- Arrow A (IT as a Product of Human Action): This arrow shows that human actors influence IT by designing, developing, and implementing it based on organizational goals, standards, and values. For example, a consulting firm’s knowledge management system is created to capture and disseminate successful practices, embodying the institution’s priorities.

- Arrow B (IT as a Medium of Human Action): This arrow reflects IT’s role as a tool that facilitates and constrains human action. A project management tool, for instance, streamlines workflows but also imposes a rigid structure, illustrating how IT shapes human actions by enabling some behaviors while restricting others.

- Arrow C (Conditions of Interaction with IT): Institutional properties, like design standards, policies, and resources, set conditions for how people use IT. An organization might restrict access to specific software features to ensure compliance, affecting how employees interact with IT.

- Arrow D (Consequences of Interaction with IT): This arrow shows that interaction with IT can alter institutional properties. When employees use IT in unexpected ways, they may gradually reshape norms and power dynamics within the organization, demonstrating the feedback effect between human actions, IT, and organizational structures.

How IT Impacts the Core Structures of Structuration Theory

Orlikowski and Robey’s model emphasizes that IT can influence each of the three core structures in structuration theory:

- Structure of Signification (Meaning):

- IT systems impact shared meanings within an organization. For instance, a consulting firm’s knowledge management system documents successful project strategies, shaping employees’ perceptions of what “good practice” entails. This reinforces the organization’s values and provides a shared understanding of best practices, impacting the structure of signification.

- Structure of Domination (Power):

- IT can reinforce or alter power dynamics by controlling access to resources. For example, if certain employees have exclusive access to customer data, they gain influence over customer-related decisions. Moreover, decisions about which IT projects to fund reflect the existing power structure, as resource allocation decisions often favor those with greater authority.

- Structure of Legitimation (Norms):

- IT enforces organizational norms by embedding rules within its design. For example, a university’s course registration system might prevent students from enrolling in more than five courses per semester, codifying an institutional policy. By programming such constraints, IT reinforces norms and shapes what is seen as acceptable behavior.

Implications for Organizations and Research

Orlikowski and Robey’s adaptation of structuration theory provides a valuable framework for studying how technology and organizations co-evolve. Here are the key implications:

- Dynamic Structures: Institutional structures are not static but evolve as people use IT. IT facilitates certain actions while constraining others, and how people use IT can reshape organizational structures over time.

- IT as Enabler and Constraint: IT serves as both a tool and a control mechanism. It enables certain actions while imposing limits, reflecting the dual nature of structuration where actions are both enabled and constrained by structure.

- Feedback Loops: The model illustrates a continuous feedback loop where human action, IT, and organizational structures influence each other. This dynamic interaction explains how organizational norms and power dynamics evolve as people use technology.

- Multi-Level Analysis: Structuration theory provides a multi-level framework, bridging individual behaviors and institutional structures. It encourages looking at both the micro-level (individual IT use) and macro-level (organizational culture) to understand the broader impact of technology.

Conclusion: Structuration Theory as a Meta-Theory for Organizational Analysis

Structuration theory, as extended by Orlikowski and Robey, is a powerful framework for understanding the complex interplay between individuals, technology, and organizational structures. It highlights that:

- Structures both constrain and enable actions, while individual actions continuously reshape those structures.

- IT is a product of human action and a medium for further actions, influencing and being influenced by the organizational context.

- This framework is flexible and adaptable, providing a high-level view that can support various research agendas in Information Systems and organizational studies.

By applying structuration theory to IT, Orlikowski and Robey reveal technology’s profound role in shaping organizational life. This perspective moves beyond viewing IT as a passive tool, recognizing it as an active force in the evolution of organizational structures, culture, and power dynamics. Structuration theory thus remains relevant for researchers and practitioners seeking to understand and navigate the impact of technology on organizational dynamics.4o

Leave a Reply